|

|

|

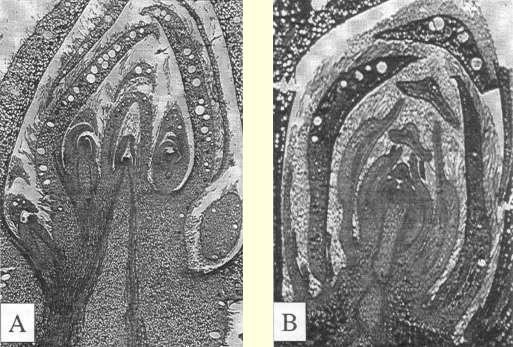

| Fig. 1 Microscopic images of Metrosideros excelsa buds in August showing (A) a floral bud with cymule development in bud scale axils, and (B) a vegetative bud with leaf formation by apical meristem and little axillary development. Magnification l0x. |

Flowering pohutukawa in containers

By studying plants in the field under natural conditions, we believed that a shortening daylength was the key environmental factor leading to floral development. We did not know at that stage whether the lowered temperature that buds experience in winter was important for subsequent flowering. To answer this question, we grew pohutukawa plants over winter in greenhouses that were artificially heated, or had daylength artificially extended. As expected, plants grown under long days did not flower well; they did not flower at all if they were kept warm over winter while receiving long days. Plants flowered when allowed to grow under short daylengths, and flowering was better when the plants were allowed to experience cool winter temperatures.

Conclusion

With these pieces of information we are drafting a protocol for the control of flowering in pohutukawa, paving the way for their development as flowering pot plants that can be produced to schedule. Since then we have extended our knowledge of the light environment required to enhance flowering. We have also tested ways of accelerating or slowing flowering by modifying the temperature regime in which the plants are grown after bud break. There are numerous Metrosideros. We are progressing our research with several M. excelsa cultivars, including M. excelsa cv. Vibrance, and with those from other parts of the Pacific.

References

Clemens, J., Henriod, R. E., Bailey, D. G., and Jameson, P. E. 1999a: Vegetative phase change in Metrosideros. Shoot and root restriction. Plant Growth Regulation 28: 207-214.

Clemens, J., Jameson, P. E., and Henriod, R. E. 1999b: Hastening and controlling flowering in Metrosideros. International Plant Propagators Society Combined Proceedings 48: 80-83.

Henriod, R. E., Jameson, P. E. and Clemens, J. 2000: Effects of photoperiod, temperature and bud size on flowering in Metrosideros excelsa (Myrtaceae). Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 75: 55-61.

![]()

- View

this paper as a PDF of the original proceedings

- Full

conference proceedings available as a hardcopy from the RNZIH

Reproduced from: New Zealand Plants and their Story

Proceedings of a conference held in Wellington, 1-3 October 1999

ISBN 0-9597756-3-3

Home | Journal

| Newsletter | Conferences

Awards | Join

RNZIH | RNZIH Directory | Links

© 2000–2026 Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture

Last updated: April 25, 2004