| Pennantia

baylisiana Reproduced from an article by Professor G. T. S. Baylis From The New Zealand Garden Journal (Journal of the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture), Vol. 2, No. 1, March 1997, pp. 12-13.  T.

F. Cheeseman was an early Director of the Auckland Museum. He was

also the first botanical explorer of the Three Kings Islands. On his

visits in 1887 and 1889 he had only a few hours ashore, yet he found

six new plants. A more thorough search was clearly warranted but it

was not until 1945 that the Museum arranged for a scientific party

to camp on the main island. I was the botanist.

By this time wild

goats had eaten the place out. Part was closely browsed grass but

most was kanuka forest or scrub. Cheeseman's novelties survived in

small numbers beyond browse range. It was easy to see that the grassland

offered nothing new, but the kanuka canopy was broken here and there

by other textures and shades of green. I located these places by climbing

trees at every vantage point and reached them deviously via bluffs

and screes since except in the main valley they were, even for goats,

a bit inaccessible. T.

F. Cheeseman was an early Director of the Auckland Museum. He was

also the first botanical explorer of the Three Kings Islands. On his

visits in 1887 and 1889 he had only a few hours ashore, yet he found

six new plants. A more thorough search was clearly warranted but it

was not until 1945 that the Museum arranged for a scientific party

to camp on the main island. I was the botanist.

By this time wild

goats had eaten the place out. Part was closely browsed grass but

most was kanuka forest or scrub. Cheeseman's novelties survived in

small numbers beyond browse range. It was easy to see that the grassland

offered nothing new, but the kanuka canopy was broken here and there

by other textures and shades of green. I located these places by climbing

trees at every vantage point and reached them deviously via bluffs

and screes since except in the main valley they were, even for goats,

a bit inaccessible.In these clumps such

things as puriri, mahoe and mangeao persisted and I soon found the

liane Tecomanthe speciosa and the rangiora with a corky

trunk like a cabbage tree - Brachyglottis arborescens.

The last little grove that I investigated lay near the highest point

of the island down a scree of boulders about 200m above the sea.

I was drawn to it by what looked like a karaka. I was soon gazing

upon it in disbelief since a third find seemed too much to expect.

But this was no karaka - its leaves were larger and recurved strongly

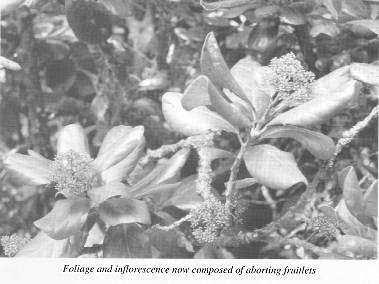

in the sun, its bunches of small green flowers sprang from the bare

branches below the leaves and there were no big berries - indeed

none at all. Dr W. R. B. Oliver, our

last true biologist equally authoritative about animals or plants

was anxious to identify my finds and I sent them to him. Lacking

time and experience, I feared I might blunder by getting a family

wrong. This danger proved real indeed, for Oliver himself put the

pseudo-karaka in the Anacardiaceae, which is close to the karaka

family, whereas had I been able to send fruits he would have realized

that the resemblance to karaka is misleading, the proper family

being Icacinaceae to which Pennantia belongs. It was a European botanist working with herbarium sheets who realised that the Three Kings specimens were Pennantia: indeed concluded that the tree was just a stray P. endlicheri from Norfolk Island. But herbarium sheets don't tell all - thicker leaves recurving curiously in the sun, stouter stems and flowers on leafless branches rather than at the ends of twigs so distinguish the Three Kings tree, that the two have little resemblance. So when our Flora is next revised either the definition of Pennantia will be broadened to accommodate cauliflory (flowers arising on old wood) or Oliver's genus Plectomirtha will reappear as a member of the Icacinaceae. The former seems the wiser course as P. baylisiana does occasionally flower at a branch tip. Moreover, the objective of taxonomy is to synthesise and there is no synthesis when a species has a genus to itself.

Propagating this lone

and sterile tree, not in the best of health because of insect damage,

seemed urgent. There was a detachable shoot at its base which took

root in a damp sheltered place in my Dunedin garden and is now very

like its parent with four slender trunks. But its canopy trimmed

by occasional frost rather than repeated salty gales is taller (7m). While I was unsure that this shoot had really rooted, I was worried by failure both at the Plant Diseases Division at Mt Albert and at Duncan and Davies, New Plymouth to strike cuttings from the crown. I asked George Smith the chief propagator at New Plymouth what I might do to provide better cuttings. "Cut the tree down" he said, and while I shuddered at the thought he explained that he was confident about rooting shoots from the stump. But would there be any? Well, the tree had four trunks so I dared to sever one. A year later the shoots were there, the Naval launch on which I was a guest gave them a quick passage to New Plymouth which happened to be its next port and Mr Smith soon placed the survival of "Plectomirtha" beyond doubt.

|

Home | Journal

| Newsletter | Conferences

Awards | Join

RNZIH | RNZIH Directory | Links

© 2000–2026 Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture

Last updated: March 1, 2021